I’m sure that you’ve noticed the lack of meaningful posts to this blog in the recent past, and I’m sorry that your lives have been sadly devoid of the warm glow that makes life worth living as a result. (My wife assures me that you haven’t noticed.) “We understand completely,” I hear the throngs acclaim, “how could we miss the recent evidence of the overwhelming effort that was obviously required to bring The Problem With God to fruition, now available at Amazon and for the Nook?” (They have no idea what I’m referring to, my wife informs me, trying to set my mind at ease.) Or perhaps it was the press of getting ready for the craziness that is the holiday season, you conjecture. (They don’t conjecture, my wife interjects, because they haven’t noticed. If they noticed, they wouldn’t care, she reassures me. And by the way, she adds, there is no ‘they’ anyway. There is only the empty, black nothingness that lives behind my computer screen, she smiles. She’s my rock.)

While I certainly appreciate your willingness to excuse my lack of creative fecundity (or should that be, fecund creativity?), I feel compelled to explain the real reason for my paucity of posts. I can’t see worth shit.

It’s true. I’m writing this by sensing the individual letters by pressing my nose against the screen. (Consonants smell like toast, vowels like fruit. The letter ‘y’ smells like wet dog.) Obviously, this is a slow and inexact practice. Actually, this post would’ve gone up three days ago except the ‘save’ button smells exactly like ‘delete.’

Here follows a tale of yearning, fear, and cosmic payback; certain to stimulate your need for schadenfreude and ‘thank-God-it’s-Geller-and-not-me-or-someone-I-really-care-about’ relief that is so especially appropriate for this holiday season:

Yearning: I have worn glasses since I was seven years old. My mother actually claims that I was born wearing glasses, which made for a particularly painful delivery for which I was never properly appreciative. I don’t believe this, however, as one of my most profound childhood memories is of that exact day in the third grade at Einstein Elementary School when I joined the rest of my fresh-faced classmates in lining up for eye exams in the cafeteria during recess. How clearly I recall the looks of sad compassion on the faces of the grownups as they shook their heads and announced that I had failed my exam. Failed! That was the exact term they used, the word they checked off on the mimeographed form they made me hold all day, staring at it (cruelly blurry, all those mimeos were blurry), finally carrying it home to present to my disappointed parents. They shook their heads in consternation and I burst into tears at the kitchen table. It was the first test that I had ever failed. Not to worry, my parents reassured me, you can just wear your bother’s hand me down glasses.

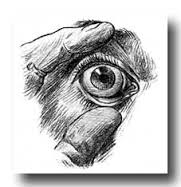

Since that day, I have worn glasses. I never complained, despite seeing the world through someone else’s corrective lenses. Since I didn’t know any better, I accepted the distortion of the world about me, the crazed funhouse mirror appearance of the adults looming over me, the facial expressions of those I loved always looking like something out of that Twilight Zone episode that gave everyone nightmares. (In the Eyes of the Beholder, I think it was called. This will prove ironic.) A lifetime of watching my glasses fly across the room whenever some perceived insult led to a slap in the face, of watching my glasses fly onto the infield grass of the Matterhorn ride at Disneyland (a story for some other time), of a hard packed snowball with my glasses in the middle thrown into the windshield of the principal’s car as it sped from the parking lot. The principal returned my glasses but he was not happy about it, not one bit. And they never quite fit right after that.

For just shy of a half-century I happily accepted my facial appendage. I must admit, however, that I yearned to see the time on the bedside clock every morning. I yearned to actually see through a telescope, a microscope, an otoscope, an opthalmoscope, and not just to pretend I could see what everyone else could see. I yearned for clarity. But I always kept this yearning to myself. And I never let this yearning get so out of control that I ever, ever considered getting contacts. Never.

Fear: The entire concept of contact lenses horrifies me. The name horrifies me. I mean, the “contact” the name refers to is your eyeball. I don’t do eyedrops, no way in Hell I’m sticking a piece of jellied plastic in my eye unless it’s kicked up by the rear wheel of a passing cement truck. I’ve cleared out my eye doctor’s waiting room on several occasions because of the screaming elicited every time he tries to measure my intraocular pressure. “Just a puff of air,” my ass. That thing is a medieval torture apparatus.

There came a day, however, when the yearning for clarity was joined by a dangerous disability to see certain items at night; things like moving cars, traffic lights, and pedestrians. A certain small dog, I think. Enough is enough, I believed. I deserve, I need, to see! This feeling was only strengthened by an unfortunate episode in the operating room recently. I had the privilege to operate upon an optholomologist. Nothing major. As he was lying on the OR table before surgery, I engaged him in lighthearted banter, in the fashion of reassuring him and setting him at ease. (Doctors are the worst patients.) I’m thinking of having surgery soon myself, I said to him conversationally. Really, he asked, what kind of surgery? Well, I admitted, these cataracts are really starting to bother me and I was thinking–the guy sat bolt upright on the table. “You can’t see?” he asked me. “I think we should cancel this surgery. You should not be telling me such things. I think we should reschedule.” I’m pretty sure he was kidding. It didn’t really matter anyway, since at that moment the anesthesia hit him and he fell back, unconscious. I don’t think he remembered the conversation afterwards.

It bothered me though. He might be right. I should be able to see. I want to see. So I went ahead with the cataract operation. The world went dark.

Cosmic Payback: The surgery went fine. Before the operation I told the anesthesiologist, a friend of mine, that if I’m awake, I’m screaming. (Doctors are the worst patients.) When I eventually awoke face down in the parking lot, my old milky, calcified lens had been plucked from its dusty lair and replaced with a shiny new piece of plastic. Never felt a thing. The next day, my blurry ophthalolomomolologist was pleased with the result. [Brief Aside: It is my theory that while constantly smiling and chipper, all opohthlolkmologistolists are secretly angst ridden and angry because even they really have no idea how to spell the name of their profession.] I was also fairly pleased, except for the little inconvenience that I couldn’t see a thing. “Yeah,” he explained, “that’s to be expected. You’ll need to wear a contact lens in the other eye for a month until we operate on that one.” “I’m sorry,” I said, “I thought you said something just now about contact lenses. So much for my other senses taking up the slack, huh, doc?” “No, really,” Blurry Bob confirmed (I don’t think I actually called my opthalcomologist that to his face, I was just upset and it seemed an appropriate moniker at the time. I may have called him “The Butcher of my Eyes” once or twice, though. Like I said, I was blind, and upset.) He explained the dark, arcane science of quantum optical physics that made no sense to me but ended with the cosmic certainty that my glasses were now useless. My mind could not reconcile the new view from my left eye, soon to be perfect in viewing things on the horizon but only magnified fuzziness anywhere within shouting distance, with the lifelong image from the right eye, nice and sharp up close but gelatinous and unformed beyond the end of my arm’s reach. An insurmountable dichotomy that will destroy my mind, he explained. “We’ll just set you up for contact lens instruction.” Yeah, right.

I stumbled into the optician’s subterranean lair and began screaming at “Hello.” The instruction did not go well. While the instructor was nice and patient (at first, though with a disturbingly evil, maniacal laugh), I knew she was starting to get a bit testy with my lack of ability to shove my hand in my eye when she suggested that my wife, a veteran contact lens user of decades, could do it for me. Sure, that sounds like fun. Then they started to talk about “plungers” and showed me a rusty ice pick she uses to remove “a displaced lens,” whatever that means. Something about the lens ending up behind my eye and stuck to the frontal lobe of my brain. Hers was a unique and effective teaching technique. I left sightless, wounded, and with a jelly blob folded into my one good eye. But I’m still reluctant to let my wife of thirty years scrape this thing off my eyeball. She is enthusiastic to help, however.

I can’t wait to get the other eye operated on. In the meantime, I’m coming up with reassuring new explanations when my patients ask why I was just led into the OR by a seeing eye dog.