Worth a couple minutes of your time:

Support your local library.

I’m so proud of my Mom. She told me last night that she had gotten a call earlier in the evening (middle of dinner, of course) from a woman asking her to confirm her banking and credit card information. Despite the woman insisting that it was perfectly fine to tell a complete stranger on a cold call your every vital identifying fact, my mother demurred. At 87, she’s still too polite to just hang up on the pirate, but she knows a scam when she hears one. Good for you, I told her. But listen to this. Here’s a new one.

I’ve had my “identity” stolen at least four times over the past five years. The first time, I was upset. I got a call from my credit card company asking me if I was buying a lot of stuff in Tennessee. Never been there. The nice guy from the bank actually was able to tell me the name of the guy who was buying stuff on my account and the address that he was having all the stuff sent to. “So, you’re going to have the police in Tennessee pick him up?” I asked naively. “Naw, of course not,” the bank guy said. “We’ll just cancel out the card and send you a new one.” At the time, I was rather indignant that no one was going after the guy who had stolen my “identity.” Having gone through this process a few more times now, I’ve come to be more blasé about the whole deal. Happens every day, I know.

But this is different.

A close relative called up the other day, quite upset. It seems that she had just received an email from her bank notifying her that the credit card that she had requested was in the mail to her home. She hadn’t ordered any credit card. She immediately called the bank and spoke to a representative. “Oh,” he admonished her, “you probably filled out the application the last time you were in the branch and just forgot.” “No way,” she said. “I haven’t been inside a bank in years.” She does all her banking online. He agreed that something was amiss and cancelled the card. He went on to recommend that she sign up for the bank’s credit monitoring service, in view of this near-miss identity theft. Only $14/month. She was so upset by the incident that she agreed to the service, grateful that the whole mess had been caught before any real damage had been done.

“Hold it,” I said, interrupting her story at this point. “The email said the card was in the mail to you?” “Yeah.” “But that makes no sense,” I said. Being old, I am an expert in all things. Including having one’s “identity” stolen. “Why would someone have the stolen card sent to you? They steal a bunch of identities and have the cards sent to a post office box. Then they use the cards for a day or two before they’re cancelled. Makes no sense.”

She was quiet for a minute. “I’ll call you right back,” she said. She called the bank again, getting a different service representative. She explained her previous exchange and asked, rather pointedly, what was going on. There was a pregnant pause before the bank guy responded. “It seems,” bank guy explained, “that one of our employees initiated the request for the new card.” He went on to explain that it was not the bank’s policy to do such a thing, of course, but there were incentives to move more credit cards, you understand, and of course he would be certain that the card was indeed cancelled. Oh, and he’d be reporting the entire sordid affair to his supervisor.

“Of course,” my close relative said. “And what about the credit reporting service that you guys just sold me by scaring the shit out of me?”

“Oh, you sure you don’t want to go ahead with that? Just in case?”

I’m sure that you’ve noticed the lack of meaningful posts to this blog in the recent past, and I’m sorry that your lives have been sadly devoid of the warm glow that makes life worth living as a result. (My wife assures me that you haven’t noticed.) “We understand completely,” I hear the throngs acclaim, “how could we miss the recent evidence of the overwhelming effort that was obviously required to bring The Problem With God to fruition, now available at Amazon and for the Nook?” (They have no idea what I’m referring to, my wife informs me, trying to set my mind at ease.) Or perhaps it was the press of getting ready for the craziness that is the holiday season, you conjecture. (They don’t conjecture, my wife interjects, because they haven’t noticed. If they noticed, they wouldn’t care, she reassures me. And by the way, she adds, there is no ‘they’ anyway. There is only the empty, black nothingness that lives behind my computer screen, she smiles. She’s my rock.)

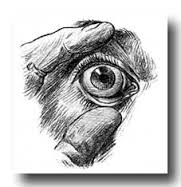

While I certainly appreciate your willingness to excuse my lack of creative fecundity (or should that be, fecund creativity?), I feel compelled to explain the real reason for my paucity of posts. I can’t see worth shit.

It’s true. I’m writing this by sensing the individual letters by pressing my nose against the screen. (Consonants smell like toast, vowels like fruit. The letter ‘y’ smells like wet dog.) Obviously, this is a slow and inexact practice. Actually, this post would’ve gone up three days ago except the ‘save’ button smells exactly like ‘delete.’

Here follows a tale of yearning, fear, and cosmic payback; certain to stimulate your need for schadenfreude and ‘thank-God-it’s-Geller-and-not-me-or-someone-I-really-care-about’ relief that is so especially appropriate for this holiday season:

Yearning: I have worn glasses since I was seven years old. My mother actually claims that I was born wearing glasses, which made for a particularly painful delivery for which I was never properly appreciative. I don’t believe this, however, as one of my most profound childhood memories is of that exact day in the third grade at Einstein Elementary School when I joined the rest of my fresh-faced classmates in lining up for eye exams in the cafeteria during recess. How clearly I recall the looks of sad compassion on the faces of the grownups as they shook their heads and announced that I had failed my exam. Failed! That was the exact term they used, the word they checked off on the mimeographed form they made me hold all day, staring at it (cruelly blurry, all those mimeos were blurry), finally carrying it home to present to my disappointed parents. They shook their heads in consternation and I burst into tears at the kitchen table. It was the first test that I had ever failed. Not to worry, my parents reassured me, you can just wear your bother’s hand me down glasses.

Since that day, I have worn glasses. I never complained, despite seeing the world through someone else’s corrective lenses. Since I didn’t know any better, I accepted the distortion of the world about me, the crazed funhouse mirror appearance of the adults looming over me, the facial expressions of those I loved always looking like something out of that Twilight Zone episode that gave everyone nightmares. (In the Eyes of the Beholder, I think it was called. This will prove ironic.) A lifetime of watching my glasses fly across the room whenever some perceived insult led to a slap in the face, of watching my glasses fly onto the infield grass of the Matterhorn ride at Disneyland (a story for some other time), of a hard packed snowball with my glasses in the middle thrown into the windshield of the principal’s car as it sped from the parking lot. The principal returned my glasses but he was not happy about it, not one bit. And they never quite fit right after that.

For just shy of a half-century I happily accepted my facial appendage. I must admit, however, that I yearned to see the time on the bedside clock every morning. I yearned to actually see through a telescope, a microscope, an otoscope, an opthalmoscope, and not just to pretend I could see what everyone else could see. I yearned for clarity. But I always kept this yearning to myself. And I never let this yearning get so out of control that I ever, ever considered getting contacts. Never.

Fear: The entire concept of contact lenses horrifies me. The name horrifies me. I mean, the “contact” the name refers to is your eyeball. I don’t do eyedrops, no way in Hell I’m sticking a piece of jellied plastic in my eye unless it’s kicked up by the rear wheel of a passing cement truck. I’ve cleared out my eye doctor’s waiting room on several occasions because of the screaming elicited every time he tries to measure my intraocular pressure. “Just a puff of air,” my ass. That thing is a medieval torture apparatus.

There came a day, however, when the yearning for clarity was joined by a dangerous disability to see certain items at night; things like moving cars, traffic lights, and pedestrians. A certain small dog, I think. Enough is enough, I believed. I deserve, I need, to see! This feeling was only strengthened by an unfortunate episode in the operating room recently. I had the privilege to operate upon an optholomologist. Nothing major. As he was lying on the OR table before surgery, I engaged him in lighthearted banter, in the fashion of reassuring him and setting him at ease. (Doctors are the worst patients.) I’m thinking of having surgery soon myself, I said to him conversationally. Really, he asked, what kind of surgery? Well, I admitted, these cataracts are really starting to bother me and I was thinking–the guy sat bolt upright on the table. “You can’t see?” he asked me. “I think we should cancel this surgery. You should not be telling me such things. I think we should reschedule.” I’m pretty sure he was kidding. It didn’t really matter anyway, since at that moment the anesthesia hit him and he fell back, unconscious. I don’t think he remembered the conversation afterwards.

It bothered me though. He might be right. I should be able to see. I want to see. So I went ahead with the cataract operation. The world went dark.

Cosmic Payback: The surgery went fine. Before the operation I told the anesthesiologist, a friend of mine, that if I’m awake, I’m screaming. (Doctors are the worst patients.) When I eventually awoke face down in the parking lot, my old milky, calcified lens had been plucked from its dusty lair and replaced with a shiny new piece of plastic. Never felt a thing. The next day, my blurry ophthalolomomolologist was pleased with the result. [Brief Aside: It is my theory that while constantly smiling and chipper, all opohthlolkmologistolists are secretly angst ridden and angry because even they really have no idea how to spell the name of their profession.] I was also fairly pleased, except for the little inconvenience that I couldn’t see a thing. “Yeah,” he explained, “that’s to be expected. You’ll need to wear a contact lens in the other eye for a month until we operate on that one.” “I’m sorry,” I said, “I thought you said something just now about contact lenses. So much for my other senses taking up the slack, huh, doc?” “No, really,” Blurry Bob confirmed (I don’t think I actually called my opthalcomologist that to his face, I was just upset and it seemed an appropriate moniker at the time. I may have called him “The Butcher of my Eyes” once or twice, though. Like I said, I was blind, and upset.) He explained the dark, arcane science of quantum optical physics that made no sense to me but ended with the cosmic certainty that my glasses were now useless. My mind could not reconcile the new view from my left eye, soon to be perfect in viewing things on the horizon but only magnified fuzziness anywhere within shouting distance, with the lifelong image from the right eye, nice and sharp up close but gelatinous and unformed beyond the end of my arm’s reach. An insurmountable dichotomy that will destroy my mind, he explained. “We’ll just set you up for contact lens instruction.” Yeah, right.

I stumbled into the optician’s subterranean lair and began screaming at “Hello.” The instruction did not go well. While the instructor was nice and patient (at first, though with a disturbingly evil, maniacal laugh), I knew she was starting to get a bit testy with my lack of ability to shove my hand in my eye when she suggested that my wife, a veteran contact lens user of decades, could do it for me. Sure, that sounds like fun. Then they started to talk about “plungers” and showed me a rusty ice pick she uses to remove “a displaced lens,” whatever that means. Something about the lens ending up behind my eye and stuck to the frontal lobe of my brain. Hers was a unique and effective teaching technique. I left sightless, wounded, and with a jelly blob folded into my one good eye. But I’m still reluctant to let my wife of thirty years scrape this thing off my eyeball. She is enthusiastic to help, however.

I can’t wait to get the other eye operated on. In the meantime, I’m coming up with reassuring new explanations when my patients ask why I was just led into the OR by a seeing eye dog.

During my training, I spent a couple of months at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. Parkland has always been a leading institution in trauma care and I was there to learn from the best. It was, of course, the hospital that cared for President Kennedy when he was assassinated fifty years ago today. I still clearly recall that day decades earlier, and the pervasive sadness that followed for weeks thereafter. It was a sudden and tragic wrenching of the world for all of us, even those too young like myself to fully comprehend what had happened or why. Actually, the most harrowing part of the whole ordeal is that none of the grown-ups seemed to know why, either. I recall still the sense of confusion and of becoming unmoored from our previously happy lives. Whenever I confront this event, I still feel a deep sense of loss and unease. We still don’t know why.

Parkland does not shy away from its history in this event. I worked for two months in the large Emergency Department, lovingly referred to as “The Pit.” It was still run by the surgical residents. When I was there, I worked in the same resuscitation rooms where the victims that day were treated. A plaque recognizes the event. During my rotation, I had the privilege of listening to one of the participants relate the events of the tragic day. His story, as I recall it, follows.

The work in the Pit was steady, as was usual for a Friday. We were all aware, of course, that the President was in town, but nobody gave the fact a moment’s thought. We were just doing our usual work when a clerk came over to tell me that she had just gotten a call saying that the President was being brought over by ambulance. It was 1963–there was no radio communication between the hospital and the ambulance services. She didn’t know who had called or if it might be a prank of some kind. I called over my Chief Resident to tell him about the phone call. “What do you want to do?” I asked him. “Should I call the attending?”

“We better wait and see,” he said. “Probably somebody’s idea of a joke.”

So we waited. When we didn’t hear anything more, I went back to taking care of the minor injuries that was the usual fare in downtown Dallas. Suddenly, the PA announced that a trauma was at the dock. I looked at my chief, who had suddenly become very pale. We positioned ourselves to receive the patient and the big double doors burst open. A patient on a stretcher was pushed in rapidly by an army of ambulance technicians. My chief stopped them to assess the patient, a middle aged white male with an obvious severe gunshot wound. With relief, he announced, “It’s not Kennedy. Take him to Trauma Bay One.” The nurses wheeled the man into the resuscitation bay and we began our assessment. None of us recognized the victim to be Governor Connolly. As we were working, somebody announced through the doorway that a second victim was arriving.

“You take it,” the Chief said to me. I ran out just as another victim was wheeled into Trauma Bay Two. I bent over the man to see President Kennedy, the back of his head nearly shot off from a severe gunshot wound. I started the resuscitation protocol.

Within minutes, attending surgeons of every specialty flooded into the emergency department. We were quickly pushed aside. Amidst a flurry of activity, Kennedy and Connolly disappeared up the elevators to the operating rooms. The chief and I sat at the desk in the Pit. The ER was quiet and empty of patients, as they had all been removed during the crisis. With no patients to care for, we all just sat, many of the staff crying. I just stared at the trail of blood that was still on the floor leading out to the elevators. “Somebody should clean that up,” I thought.

The reason I don’t carry a gun has nothing to do with my political views, the NRA, or the second amendment of the Constitution. It has nothing to do with the fact that my professional life has involved caring for hundreds of victims of gun violence. I’ve operated on a lot more people that have been assaulted by McDonald’s fries and bacon cheeseburgers than guns. There are three reasons that I don’t own a gun. These reasons are fact, are unassailable arguments against my owning a gun, and almost never come up in discussions of gun ownership. The three reasons that I don’t own a gun are:

i. Guns only work when you pull the trigger.

ii. Guns only do one thing.

Very early in my surgical training, I was standing next to one of my fellow residents in the OR locker room as we changed out of our scrubs at the end of the day, both getting ready to head home. We were working at an inner city hospital in the late eighties, the place and time of a significant peak in gun violence. During summer on-call nights, I remember sitting on the loading ramp of the ER hanging out with the cops and paramedics, shooting the breeze and listening to the steady pop of handgun fire from across the city, the occasional tat-a-tat of an Uzi; some of it sounding like just a block or two away. It was Mogadishu, but with more snow and great Coney Island hotdogs. Anyways, I remember being in my first year as a resident and standing next to this second year as we got ready to leave, putting my keys back in my pocket as I noticed the other guy take a small handgun from his locker shelf and tuck it into his pants. I was shocked. I don’t think I had ever seen a “regular” person with a gun before. “You carry a gun?” I asked him.

“Yeah,” he said, slamming the locker. “You don’t?” I shook my head. “Well, good luck with that,” he said. As he left, I considered the fact that we were working in a very dangerous area, that my apartment a ten minute drive away was in an equally dangerous neighborhood, that one of our surgical attendings had his Camaro stolen twice in the past six months from the hospital parking garage. Just that day, there had been another newspaper article on the rising frequency of carjackings on the expressway I took home to visit my parents. Actually, I thought, he might have a point. The night before, I had been forced to circle my apartment building for twenty minutes, because when I pulled into the parking lot three dudes with Uzi’s slung on their shoulders were standing in my parking spot conducting a business transaction. One of the guys had politely suggested that I come back a little later, and I had taken his advice. Maybe having a gun wasn’t such a bad idea.

I briefly thought about the concept of owning a gun. It certainly wasn’t difficult as a physician to get a concealed carry permit. But after further consideration, I realized that for me, a gun would be a mistake. At that time, I came to my conclusion based upon Reason Number One: Guns only work when you pull the trigger. If you are carrying a gun, you have to be willing to use it. And by use it, I don’t mean pulling out your piece and waving it about at a possible assailant, saying “Back off, asshole, I’ve got a gun here.” That doesn’t work. That will get you killed. Carrying an unloaded gun doesn’t work. That will get you killed. No, if you decide to carry a gun, you have to be prepared (ie., trained and practiced) and willing to shoot a person. If you are not prepared and willing to shoot a person, you are worse than foolish to carry such a device, because the other guy must assume that you are carrying your gun because you are prepared and willing to shoot him with it. He will act accordingly. Which, by the way, also applies to any interactions with cops that you might have while carrying. If you carry a gun and you are pulled over for a traffic violation (see my previous blog post Trunk Full of Human Tissue), you must maintain both hands on the top of your steering wheel, window down, and greet the friendly officer with the statement “Good evening, officer. I have a loaded handgun under my seat for which I have a license. I will not move my hands from this steering wheel until you tell me to do so.” And say it all with a smile, or else you may be shot dead for speeding. I know this, because a driver was killed in my city during my residency under just this circumstance. Carrying a gun is a responsibility that must be carefully considered.

When I considered the implications of Rule Number One, I realized that it was stupid for me to have a gun, because I wasn’t willing to use it. Oh, I know what we all think, that you’ll find yourself in a situation where a Bad Person is spraying bullets at a busload of nuns and you’ll pull that gun out and blow him away, saving the day for all. But I knew better, and I still know better. Malice of intent is not an obvious condition. If you have a gun for protection, you have to be willing to shoot first. It is not a straight forward equation. Consider the following more likely scenario: You are walking to your car in an empty parking garage after a long day at work, your family waiting for your return home. As you approach, you see a man standing next to your car. You are carrying your gun. You yell, “Hey! Get away from my car.” The guy just looks at you with a defiant and threatening expression. Do you: 1. Say to yourself, “Screw it, I’m going back inside and getting security,” or 2. Pull out your loaded weapon and aim it at the individual. Perhaps you choose option number 2, hoping that your show of force will convince the guy to leave peacefully, preferably by raising his hands in the air and muttering something apologetic. But what if that doesn’t happen? It’s pretty dark, maybe the guy doesn’t see your gun. Maybe he didn’t understand your warning because your voice has become a falsetto, or he’s not an English speaker, or he’s hard of hearing. What if the dude instead bends down? Is he reaching for the twenty dollar bill he saw on the ground and that’s why he’s next to your car in the first place, or is he now removing a loaded gun from his sock? How long are you going to wait to find out before your shoot? At what point do you feel sufficiently threatened to pull the trigger? Because if you say that you will wait until the other individual has decided to persist in his threatening actions despite being warned with your raised gun, that you will wait until he straightens up and points his own gun at you, that you would wait until he starts to approach you in a threatening manner despite your repeated warnings, then you should not be carrying a gun. You will die. If you have a loaded gun, you must be prepared to use it at some point before you are fatally threatened, or you are just making the situation more dangerous for yourself. I realized with great certainty that I would never be able to shoot somebody just because I felt threatened. Which meant that a gun in my hands was worse than useless–it was dangerous. Bad idea. If you are carrying a gun, you will have to decide to pull the trigger. You also will have to spend the rest of your life living with your decision, right or wrong.

The second fact is that guns are designed to do only one thing: Kill the person they are aimed at. These machines are very effective. Trust me, as I am an expert in this regard. I have seen the effects in great detail and on many occasions. Do not believe, when you decide to pull the trigger of your gun, that the result will be anything other than a loud noise and the other person being suddenly dead. If you don’t believe me, please ask any police officer, federal agent, or soldier. Even the most skilled and practiced professional does not claim to be able to disarm, incapacitate, or neutralize the threat of another individual by shooting to wound. And you are not a professional: If you shoot at someone, you’re going to kill him. You will spend the rest of your life living with the knowledge that you killed a person. Not comfortable with this fact, buy a Taser or carry pepper spray instead.

Finally, it is a fact that I have children. If you have children, your child will find your gun. It is inevitable. At some point, your child will know you have a gun, will know where the gun is kept, will know where the ammunition for said gun is kept, will know where the key to the trigger lock or gun cabinet is kept. Do not kid yourself into thinking that your weapon will be a secret or completely secure unless it never enters your home or car. You may realize this fact and choose to address this challenge head-on, teaching your children gun safety, that it is strictly forbidden for them to touch the weapon without your permission. Admirable, but not always sufficient, I’m afraid (see “Children and Guns: The Hidden Toll,” New York Times Sept 28, 2013 http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/29/us/children-and-guns-the-hidden-toll.html) . Children, particularly children of the male type, will feel a strong urge to disregard your rules. If you were once a male child or are the parent of a male child, you realize this fact. Not only will your child be aware of your gun and capable of obtaining it, loading it, and discharging it in your absence despite any and all of your efforts to the contrary, your child may at some point have the desire to do so. Of course, you say, I would never have a gun in the house if my child were in any way mentally or emotionally unstable. This, sadly, is a fallacious argument. Your three year old son is capable of discharging your gun but is not mature enough to consider the consequences. Your teenager is emotionally unstable by definition. If your child were to develop a mental illness, you may not be aware of this fact until it is too late. The first warning sign of your child’s depression may be the sound of a gunshot from their bedroom. You may not be aware of your child’s mental instability until you hear his name on the local news. If you have children, a gun in the house is dangerous. Period. You may choose to reduce that risk by taking all appropriate measures, but you will never eliminate it. Of course, the same thing applies to that bottle of prescription pain killers that you have on your bathroom shelf.

So that is why I don’t carry a gun. You are encouraged to come to your own decision, no problem. Just don’t ask me to let my kid have a sleep over at your house.

I haven’t lived in New York my whole life. This is important. New Yorkers–that is, those individuals born and raised in NY–are a special breed. [Pause for definition: New Yorker–an individual born and raised, having attended Public or Catholic school through high school, in one of the five boroughs. Usually Queens or Brooklyn. Sorry Upstaters, you might as well have been raised in Pennsylvania, or on the Moon.] Even if they have moved away from NY for long periods of time, these individuals return prepared; armored, fortified, energized, dauntless. Nothing about living in NY fazes these folks. For those of us who have adopted NY as our home, however, it is quite a different story. Despite residing on Long Island for close to thirty years now, I continue to wince on an almost daily basis. I wince at drivers deliberately driving through red lights in the middle of the day–because they’re driving a school bus. I wince at airport cops who bang on my car and call me things that would get you hit over the head with a beer mug in a Dallas bar because I had the nerve to slow down to pick up my daughter who’s standing right there with her luggage. I wince at the high school counselor that explains to me that “You gotta realize that maybe college ain’t for every goddamn kid just because they got a doctor for a parent, you know?” Real New Yorkers never wince. Rule Number One: Never show fear.

New York is a hard place to live. Real New Yorkers do not appreciate this fact. When informed of this unassailable truth, the New Yorker looks at you with a mixture of confusion and pity. “You from Jersey?” they may ask. But they really don’t care about your answer. Rule Number Two: Only New Yorkers can criticize New York. They don’t understand that both parents need to work two or three jobs, have Sis watch the kids almost every day, and put the weekly groceries on the credit card just to survive here. They have no clue that they could be living in a four bedroom McMansion with a live-in maid and two acres in 98% of the rest of the country for what they’re spending to barely make ends meet with the mother-in-law living in the basement and paying rent. She does, however, make her own sauce and have dinner ready almost every night. Real New Yorkers wouldn’t consider moving, because there is no where else in the world to live. Visit, sure. Maybe even for a few years. But not live.

In New York, one assumes that the car facing you at the red light will make a left in front of you as soon as the light turns. That if you want your groceries bagged, maybe you should reach over and put the groceries in the bag, why don’t you? That if you allow more than ten inches between your car and the car in front of you, somebody will cut in, maybe two cars and a bus, and that this process will continue until you realize that you are actually getting farther and farther away from your destination. That if you want to get over to take that exit, you are going to have to just close your eyes and turn the wheel as you listen for the sound of screeching metal. Rule Number Three: Never make eye contact.

New Yorkers don’t realize that there is no help in this environment. On the expressway, signs are either positioned to appear just beyond the exit you needed to take, or are rendered illegible by graffiti, or have rusted to the point of pointing in slightly the wrong direction. No matter how intelligent you are or how long you stand staring at the changing big board in Penn Station as throngs stream about you like so much spawning salmon, you will not get on the right train, and therefore you will be at least forty minutes late for your appointment, and when you do arrive you will have sweat stains under your arms and your collar will be two sizes too small for your neck. New Yorkers don’t realize that you could’ve gotten the six blocks cross town quicker by walking than by sitting in the back of a taxi that moves less than eight feet in thirty minutes despite blowing its horn continuously as the driver yells an unceasing stream of something unintelligible which you eventually realize is his hands-free cellphone conversation and not directed at you at all. They don’t realize this because New Yorkers don’t take taxis in New York. Rule Number Four: If you don’t know how to get there, you have no business being here.

It’s a great town, of that there is no doubt. The people are the best in the world. But it is a hard place to live. Rule Number Five: You have to want to be here.

The NY Times (Aug 30, 2013) reports a battlefield armor manufacturer is now marketing bulletproof inserts for children’s backpacks.

(http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/30/opinion/statehouse-swagger-in-the-gun-debate.html?hp)

I love riding my bike. Just finished riding, enjoying that special glow after a vigorous spin around the University Campus. Just sitting here, wondering if the chest pain is really anything serious.

Ever since I was a boy, I have loved riding. It was always something that I could do well enough so that there was no fear or anxiety attached to the effort. It was, actually, effortless. There was no consternation over which team I’d be on, or whether these were the guys I was playing with during that embarrassing game when I passed the basketball to the guy on the other team just because he yelled “Here!” It was unadulterated fun, combined with the fact that I could go places. Even though it was the suburbs of Detroit, so everywhere I went looked pretty much like everyplace I’d been, it was still great to ride as far away as I could before it started to get late and I’d have to turn around. I’d often leave in the morning and just ride all day, alone or with friends, just picking a direction at random and riding, stopping for nourishment at the Dairy Queen. [Note for younger readers: This was the early part of the last century, when the only thing offered by DQ was soft serve “ice cream” in three flavors: White, Brown, Twisted (combination of white and brown). They were called “flavors” but really they all tasted the same, just different colors. Jimmy Hoffa is preserved in a vat of the stuff in a basement in Rochester Hills.]

The geography of Detroit was unique in that there were almost no hills at all. Whatever hills I did encounter in my youth were inevitably downhill, long stretches that allowed miles to roll by without the need to pedal. Detroit area winds were also uniformly favorable. I cannot recall ever encountering a headwind. The wind was always at our backs, always cool and refreshing. It didn’t rain in Detroit on the weekends back then.

I don’t recall ever actually getting tired. We came home because it was late, or some TV show was coming on in an hour that we couldn’t afford to miss because it would never appear again in our lifetime. Our parents didn’t notice when we left and didn’t notice when we returned, unless by some miscalculation we were late for dinner or were thought to be cutting the lawn all afternoon.

Bicycling is more difficult now. Though my Cannondale carbon fiber Lampre Caffita Team road racing bike weighs less than my socks, for some reason the combined weight of the bike and rider is now far more difficult to get moving than that old sixty pound Schwinn I used to ride as a teenager. As I leave, I feel obligated to announce to my wife that “I’m going for a ride now,” just so she’ll know to listen for sirens in the neighborhood. I also am careful to inform her of my safe return, mostly so she can release the open heart team at the nearby University Hospital from standby status, but also so that she can see how thoroughly exhausted and sweaty I’ve become because I’ve been riding my bike.

Geography has become my enemy. My house is always several hundred feet higher when I return–it must be, because all the hills go up, never down. Any brief downhill stretches are either over pavement too broken up to allow the enjoyment of momentum or are interrupted by red lights. Lights will not turn green unless I have been trapped in my cleated pedals and fallen over, having mistimed the light. This is accompanied by the sound of car horns. Occasional recommendations to buy a car or ride on the sidewalk. Ha! There are no sidewalks here, sucker.

The real problem now, though, is the lack of oxygen. I’m not sure if it has to do with global warming or the Denveresque elevation of Long Island, but after twenty minutes of riding I’m breathing like Yaphet Kotto in Alien, just before he gets eaten. And it’s always about a hundred degrees outside, except when it’s way too cold. And the wind–I mentioned the wind, right? It’s a strange circular wind that’s always straight in my face in gusts of like eighty miles per hour, going and coming back. But it’s an oxygen-poor wind.

Still, I love to ride. I just never had to worry so much before. Like my biggest worry (I have a list in my mind entitled “My Biggest Worry.” It currently has eighteen items.), which is that I’ll die in the next ten minutes, still dressed in these ridiculous Spandex riding shorts and my LiveStrong! bicycling jersey. We have volunteer firemen here in this rural, mountainous part of Long Island, no professional paramedics. I just know if they find me dead in this outfit, these guys are posting the picture to their Twitter feed. Not the way I want to go, or go viral.

I think I’ll take an aspirin now. It couldn’t hurt.

It was a classic Superman moment. A train of seventy-two railroad cars filled with highly flammable liquid was poised precariously on a hill above a sleepy town filled with innocent Canadians. It was dark. There was no driver or attendant to witness that the airbrakes preventing the train from slipping are slowly draining pressure. The train begins to slowly roll downhill, picking up momentum as it ponderously but inevitably begins to roll faster and faster towards the center of town, disaster looming–but wait! Here he comes, streaking out of sky! A red and blue caped blur, a powerful hand braced against the lead locomotive, a grimace and then, with a squeal–all is saved, disaster averted.

Only it didn’t happen. No Superman. Instead, disaster, death, and destruction. Innocent lives lost. The classic Superman moment, one I had witnessed in comics and onscreen since my wide-eyed youth, went horribly wrong. No Superman.

At first, I hoped and believed that Superman could not save the day because he was otherwise occupied achieving even greater goodliness, saving even larger populations of threatened innocents. But I checked–it seems that North Korea had not simultaneously launched a nuclear tipped missile aimed at a New York museum at the exact moment that Lois Lane was visiting with her little nephew’s fourth grade class. The only other possible explanation, that Lex Luthor had Superman incapacitated under a geodesic dome made of Kryptonite, was also disproved by a quick Google search. No Superman.

How could it be that Evil had triumphed? How could the sinister forces of darkness and malevolence succeed, unchecked by our heroes? Such a situation is contrary to the workings of a moral universe, would require the balance beam of justice to be bent beyond all reasonable fairness. Not possible; the Fates are not so cruel.

But, hold on a second. Deep investigation reveals no Fates, cruel or otherwise, in the immediate vicinity at the time of the accident. Reviews of salient radar logs show a sky clear of evil, flying monkeys. Overhead satellite imaging clearly indicates that a demonic miasma did not dissolve the critical feedlines to the airbrakes. Not at all. No Evil, either, it seems.

No, upon further investigation it appears that a well-meaning crew of volunteer firemen, responding to a fire on the train, skillfully extinguished the blaze. They did their best, including following the protocol which required them to shut down the engine to the burning train. The engine that provided the pressure necessary to maintain the airbrakes. And then they went home.

No evil. Not even an absence of good intent. But no Superman.

It makes me sad.

My heartfelt sympathy to the families of the victims of the Canadian railway tragedy.

Requiem en pace

For a very long time, my favorite aphorism was “Don’t panic.” I am a big fan of Douglas Adams, obviously. My son and I often threaten his Mom that we’re going to get the phrase tattooed on the back of our right hands, which she no longer considers amusing. It has always seemed an apt phrase and good advice for us both. Certainly as a surgeon who specialized for a long time in trauma care, it served. It also seems appropriate for my son, who is a percussionist. It seems that unlike any other type of musician, percussionists are constantly coping. A classical violinist or horn player, performing a difficult piece in a crowded concert hall, is rarely faced with an unexpected technical challenge. They play. Percussionists, on the other hand, are frequently moving between multiple instruments, changing mallets on the fly, adjusting to alterations in tempo, tuning in mid performance. It makes me nervous just watching, but he loves it. Every performance is a challenge in real time, every note played is heard without fail by everyone in the hall. Certainly, “Don’t Panic,” has served him well throughout his career, as it has my own.

“Don’t Panic” is good advice in difficult circumstances. Whether you are faced with a patient bleeding out from a gunshot wound, a conductor who botches the crescendo, or a lethally morose robot (Hitchhiker’s reference), one must first cope. But not panicking is not sufficient. In life, as in surgery or musical performance, staying calm in the face of adversity is but the first step. The real trick, as the famed Formula One driver, Kimi Raikkonen, so elegantly stated in the title of this post, is to keep moving. When faced with a difficult challenge, a sudden catastrophe, the realized mistake–it is necessary to move forward. Carry speed. It is almost never helpful or appropriate to stop suddenly, ruminate on why the illness has happened to you, regret the decision/marriage/investment. In racing, a difficult situation is transformed into disaster by standing on the brakes, every time. The host of Top Gear, Jeremy Clarkson, once said, “Speed has never killed anyone, suddenly becoming stationary…that’s what gets you.” Carry speed.

Of course, just moving straight ahead is rarely sufficient to overcome difficult circumstances. As you are moving through trouble, the driver must see further ahead, fighting the natural tendency to become too focused on what is immediately in front. “The car goes where the eyes are looking.” Look down the road farther. Create space, change course, adapt, use a different technique–DO something. In surgery, the experienced surgeon knows that the answer is almost always “Make a bigger incision.” Better exposure, a wider approach, seeking control of the disastrous injury by extending into areas of normal anatomy is almost always the safest course. Stopping, pausing to consider, trying to figure out why one’s usual techniques have failed; these things do nothing to stop the bleeding. And there’s only so much blood one can lose before it really doesn’t matter any more.

There are a number of similarities between racing and surgery. The need for constant focus is the most concrete. In both pursuits, even a momentary lapse by the operator is often detrimental, and can at times be disastrous. Team work, skilled colleagues, luck–all are paramount in both avenues of pursuit. Even the aphorisms seem interchangeable:

“Slow hands in the fast parts, fast hands in the slow parts.” The routine parts of the operation, opening and closing, can usually be accomplished by an experienced surgeon expeditiously. Care must taken, however, when maneuvering around the pathology.

“Slow in, fast out.” Approach the pathology deliberately, intelligently choose your position as you enter the critical phase of the resection–this will make the performance of the actual maneuver straightforward, allowing an easy, controlled exit.

“The fastest line is not always the quickest.” In surgery, as in racing, it is sometimes much more efficient to take additional time in the approach, allowing the next maneuver to be performed more optimally.

“Drive your own car.” You can only be responsible for your own actions. What all the other guys are doing–the other drivers, the anesthesiologist, the other patients, the officials–is out of your control. Do what you do to the best of your ability, let the others take care of themselves or the patient.

“Make room for trouble.” Try to see the crisis developing ahead, rather than being forced to react once it happens. Create space in anticipation, extend your line around a car that looks loose entering a turn–if he goes into a spin, the added space may get you past safely. Same thing in surgery–anticipate that the infected artery may not hold your stitches, may fall apart as you try to clamp it. Extend into another body cavity if you have to: if you can’t get control of the bleeding infected aneurysm in the groin, go into the belly to get control. Anticipate and extend.

Finally, Churchill (though not a racer or a surgeon, he managed to always say it best): “When going through Hell, just keep going.”